Endangered Caribou or Wolves

A Balancing Act

Caribou in B.C.(Scientific Name: Rangifer tarandus caribou)

Did you know Caribou are built for extreme cold?

Their hooves are concave, providing traction on snow and ice, and their fur consists of both a dense, insulating underlayer and longer, hollow outer hairs that trap warm air.

Introduction

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) are an iconic species on the B.C. landscape. They have inhabited the province’s mountainous regions for over 10,000 years, emerging promptly after the retreat of the last ice age (Spalding 2000). At one time, caribou were so abundant that they were “like bugs on the landscape,” and in some places it could take up to four hours for a single herd to pass (Lamb et al. 2022, Cox 2023). Not only were these great herds emblematic of the vast, intact old-growth ecosystems they relied upon, but they in turn also provided significant subsistence, ceremonial, and cultural value to the many indigenous people occupying these territories (Lamb et al. 2022).

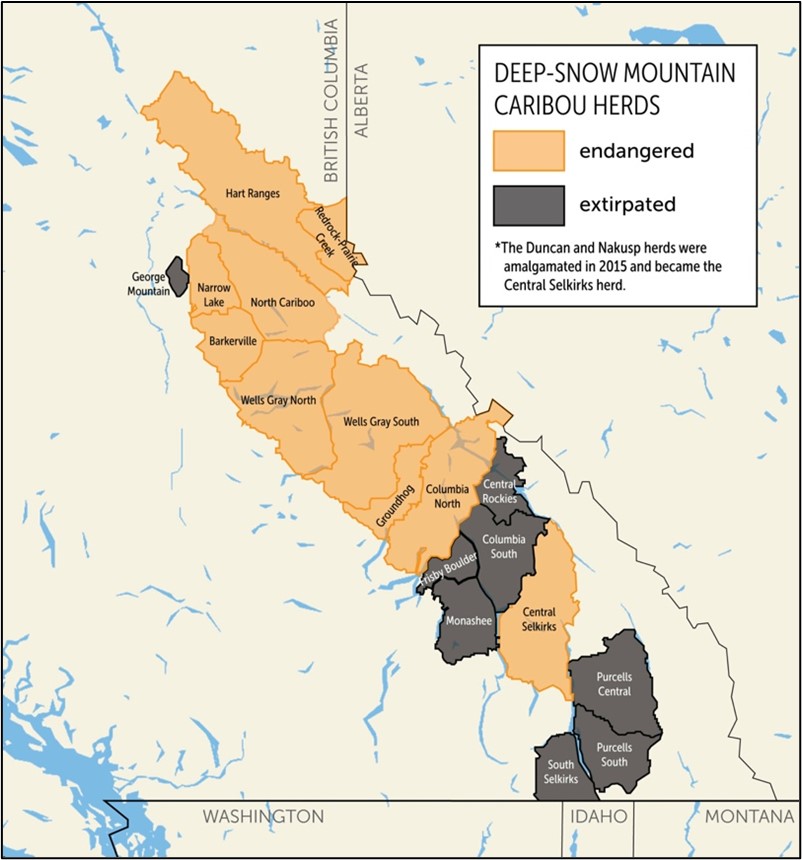

Today, the caribou tell a different story. Over a century of resource extraction, habitat loss, and human-induced climate change have drastically altered the landscapes that once provided them with such abundance. Historically totalling over 45,000 animals, British Columbia’s caribou population now consists of only 15,000 individuals, and most herds within the province are listed as ‘Threatened’ under the federal Species at Risk Act. Of the 55 herds remaining today, over 75% of them are in decline, 9 of which have already disappeared from the landscape (Lavoie 2022).

Map showing B.C.’s 18 deep-snow mountain caribou herds, of which 8 are extirpated and the remaining 10 are on the cusp of local extinction. Source: The Narwhal

Declines | Extirpation | Endangered Species

Many important questions have been raised concerning this stark decline of caribou. Why are caribou numbers falling? How can existing herds be protected, and their populations recovered? Most importantly, what do these declines say about land-use and resource management in British Columbia in general? In light of these questions, concerned citizens, indigenous communities, government, and non-government agencies have been engaging in important discussions, research initiatives, and recovery strategies to better understand caribou population dynamics and the state of caribou in B.C. What is clear is that caribou declines cannot be attributed to a single cause. Instead, several coinciding factors, including resource extraction, recreation, and climate change, have all contributed to the concerning status of these extraordinary ungulates (Lavoie 2022, Palm et al. 2020, Comer 2018).

Caribou are considered a keystone species, their presence or absence on the landscape an indication of the broader functioning of their habitats, particularly old-growth forests (Lavoie 2022, Wildsight n.d.). They have a strong affinity for intact, mature forest for forage and cover, making them particularly sensitive to any changes to or removal of these ecosystems. Mature forests are being rapidly converted to early seral conditions via forest harvest practices, mining, wildfire activity, and other human development (Lamb et al. 2022). One study found that, despite efforts under federal and provincial recovery plans, caribou have lost twice as much habitat as they have gained in the past 12 years (Nagy-Reis et al. 2020). While certain protections are in place to preserve critical habitat, including ungulate winter ranges, parks, and old growth management areas, caribou habitat continues to dwindle at a rate faster than it is being restored.

Clearcut forests in the Hart Ranges, critical old growth forest habitat for caribou in central British Columbia. Source: The Narwhal

Habitat & Population Concerns

Linear features, such as roads and seismic lines, often associated with forestry and mining, have also proven to be incredibly disruptive to caribou. Like spiderwebs weaving their way across the land, linear features mark the presence of humans like no other disturbance. Although beneficial to humans, roads, powerlines, and seismic lines have drastically altered how caribou, their competitors, and predators navigate the landscape. Linear features allow for easier access to areas that may have been difficult for predators, like wolves, to reach under natural conditions, leaving caribou more susceptible to predation. Additionally, the combination of clearcut forests and linear features transforms once unfavourable habitat for other prey species, like deer and moose, into high productivity forage areas. This influx of additional prey in caribou habitat inevitably attracts predators to areas that once would have only been accessible to the caribou (Neilson et al. 2022, Lamb et al. 2022).

Further contributing factors to the decline of caribou in B.C. include recreational activities and climate change. As humans learn to navigate the landscape more efficiently, gaining access to remote areas via helicopter, ATV, and snowmobile, we broaden our reach and impact on the ecosystems we find ourselves in. Recreational activities, including snowmobiling, heliskiing, and cat skiing foster incredible backcountry opportunities. However, they often coincide with critical caribou habitat, displacing herds from their preferred winter ranges and forcing them into more dangerous terrain, leaving them more susceptible to avalanches and other hazards (Comer 2018). Similarly, climate change can displace caribou by altering the depth of the snowpack, shifting the length and timing of each season, increasing the frequency of freeze-thaw events and the intensity of wildfires, and altering the availability of forage (Comer 2018, Nagy-Reis et al. 2020, DeMars et al. 2023).

The caribou populations in B.C. are at a critical tipping point. Achieving population recovery will take a coordinated, multi-faceted approach at local, regional, and provincial scales. Fortunately, there are fantastic organizations working diligently to find solutions. An incredible example of the work being done is that of the West Moberly and Saulteau First Nations in central British Columbia. An Indigenous-led partnership between these two nations, in collaboration with government and other groups, pairs short-term population recovery actions, predator reduction and maternal penning, with long-term habitat protection in a concerted effort to restore the Klinse-Za caribou herd. Maternal penning includes capturing a proportion of pregnant cows in late March and placing them in a monitored pen where they are safeguarded and fed until the calves are 2 months old. This drastically improves the chances of survival for young caribou. Since the start of the project in 2013, this herd has more than doubled from 38 to 101 animals (Lamb et al. 2022).

Other recovery initiatives include habitat restoration, restoration of linear features, caribou monitoring and research, and habitat protection (CMU 2017, Neilson et al. 2022, DeMars et al. 2023). A study on caribou recovery found that successful caribou conservation initiatives share one or more of the following characteristics: multiple recovery actions are implemented, recovery actions are carried out intensively, and there is a strong collaboration between Indigenous and colonial governments, industry, and other parties. The authors emphasized, however, that habitat loss is the greatest threat to caribou, and critical caribou habitat continues to be lost in Canada, despite conservation efforts (Lamb et al. 2023).

British Columbians have an important opportunity to rewrite this narrative; to tell a story of recovery rather than loss. Caribou face innumerable challenges, but their resilience is undeniable. Given the magnitude of ongoing habitat loss, land managers, scientists, governments, and citizens must consider the cumulative impacts of all human and natural disturbance on the landscape and plan management actions accordingly (Nagy-Reis et al. 2020). If we fail to do so, we will also fail the caribou.

The choice is ours to make.

Adobe Stock Image

Ecological Importance: Caribou are integral to the functioning and resilience of northern ecosystems, affecting vegetation, nutrient cycling, predator-prey dynamics, and seed dispersal. Their conservation is not only vital for the species itself but also for the overall health and balance of these unique ecosystems.

Cultural Significance

In addition to their ecological importance, caribou hold immense cultural significance for Indigenous communities in northern regions. They are a source of food, clothing, and cultural traditions, strengthening the connection between people and the land.In The News

Mountain Caribou and Wolves

Mountain Caribou are at risk of extinction. 98% of the global population of caribou lives in B.C. The current population is about 1,500, in 15 separate herds throughout B.C.

The threats to Mountain Caribou survival are loss of habitat and wolf predation.

Gov of BC FACTSHEET: Mountain caribou and wolves

Satellite imagery reveals new cutblocks are ‘nibbling away’ at the critical habitat of the endangered Columbia North caribou herd

B.C. permitted clearcut logging in the critical habitat of the Columbia North caribou herd, the sole herd out of the southern group of 17 imperiled southern mountain caribou herds to have an increasing, rather than decreasing, population.

The Narwhal

UBC study demonstrates new model for wildlife management

Researchers estimate caribou herds have declined about 40 per cent in recent decades, and in B.C.’s northeast, they’ve deteriorated 11 per cent per year.

More information on caribou and caribou initiatives in B.C.:

- Revelstoke Caribou Rearing in the Wild – website

- The Last Mountain Caribou – video

- Caribou Homeland – video

- Caribou Monitoring Unit – website

- Government of B.C., The Early History of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) In British Columbia – pdf

- Government of B.C., Caribou in British Columbia – website

References:

[CMU 2017] Caribou Monitoring Unit. 2017. Supporting Woodland Caribou Recovery in Western Canada. Retrieved from https://cmu.abmi.ca/

Comer, B. 2018. The Last Mountain Caribou. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1t3I_LN-Sg

Cox, S. 2023. ‘Death by a thousand clearcuts’: Canada’s deep-snow caribou are vanishing. Retrieved from https://thenarwhal.ca/canada-deep-snow-caribou-vanish/

DeMars, C., Johnson, C., Dickie, M., Habib, T., Cody, M., Saxena, A., Boutin, S., and R. Serrouya. 2023. Incorporating mechanism into conservation actions in an age of multiple emerging threats: The case of boreal caribou. Ecosphere 14(7), e4627.

Lamb, C., Willson, R., Richter, C., Owens-Beek N., Napoleon, J., Muir, B., McNay, R., Lavis, E., Hebblewhite, M., Giguere, L., Dokkie, T., Boutin, S. and A. Ford. 2022. Indigenous-led conservation: Pathways to recovery for the nearly extirpated Klinse-Za mountain caribou. Ecological Applications 32(5), e2581.

Lavoie, J. 2022. B.C. allows logging in critical habitat of one of the province’s sole recovering caribou herds. Retrieved from https://thenarwhal.ca/bc-caribou-habitat-wood-river-basin/

Nagy-Reis, M., Dickie, M., Calvert., M., Hebblewhite, M., Hervieux, D., Seip, D., Gilbert, S., Venter, O., DeMars, C., Boutin, S., and R. Serrouya. 2020. Habitat loss accelerates for the endangered woodland caribou in western Canada. Conservation Science and Practice 3, e437.

Neilson, E., Grandjambe, R., Abel, R., Gould, L., Degenhardt, D., and C. Chand. 2022. Testing the efficacy of linear restoration for caribou recovery in the Birch Mountains, Alberta Partnering for Restoration Success. Webinar. Retrieved from https://cmu.abmi.ca/about/caribou-ecology-and-webinar-series/

Palm, E., Fluker, S., Nesbitt, H., Jacob, A., and M. Hebblewhite. 2020. The long road to protecting critical habitat for species at risk: The case of southern mountain woodland caribou. Conservation Science and Practice 2(7), e219.

Spalding, D. 2000. The Early History of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia. Retrieved from Read More

Wildsight. n.d. Mountain Caribou. Retrieved from https://wildsight.ca/programs/mountaincaribou/